A quiet waterfront site honors the 1944 disaster, the sailors who served there, and the long fight for justice that followed.

When you think of visiting NPS sites in northern California, towering redwoods, rugged coastlines, and historic island prisons usually come to mind. But tucked along the banks of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers, about 40 miles from San Francisco, is a much smaller, lesser-known site that honors the lives lost and mistakes made in an often-overlooked story of American history. Port Chicago Naval Magazine National Monument tells the story of the 1944 military disaster that reshaped the Navy and helped spur the desegregation of the U.S. armed forces.

When America was attacked in 1942, everyday civilians answered the call with lofty aspirations of helping the war effort. Thousands of Black men joined the Navy with the intention of mirroring the heroic acts of Dorie Miller and fighting on the front lines in the Pacific theater. Unfortunately, the Navy’s racial segregation policies meant that these brave young men found themselves not overseas, but at sites throughout the mainland, including Port Chicago in California.

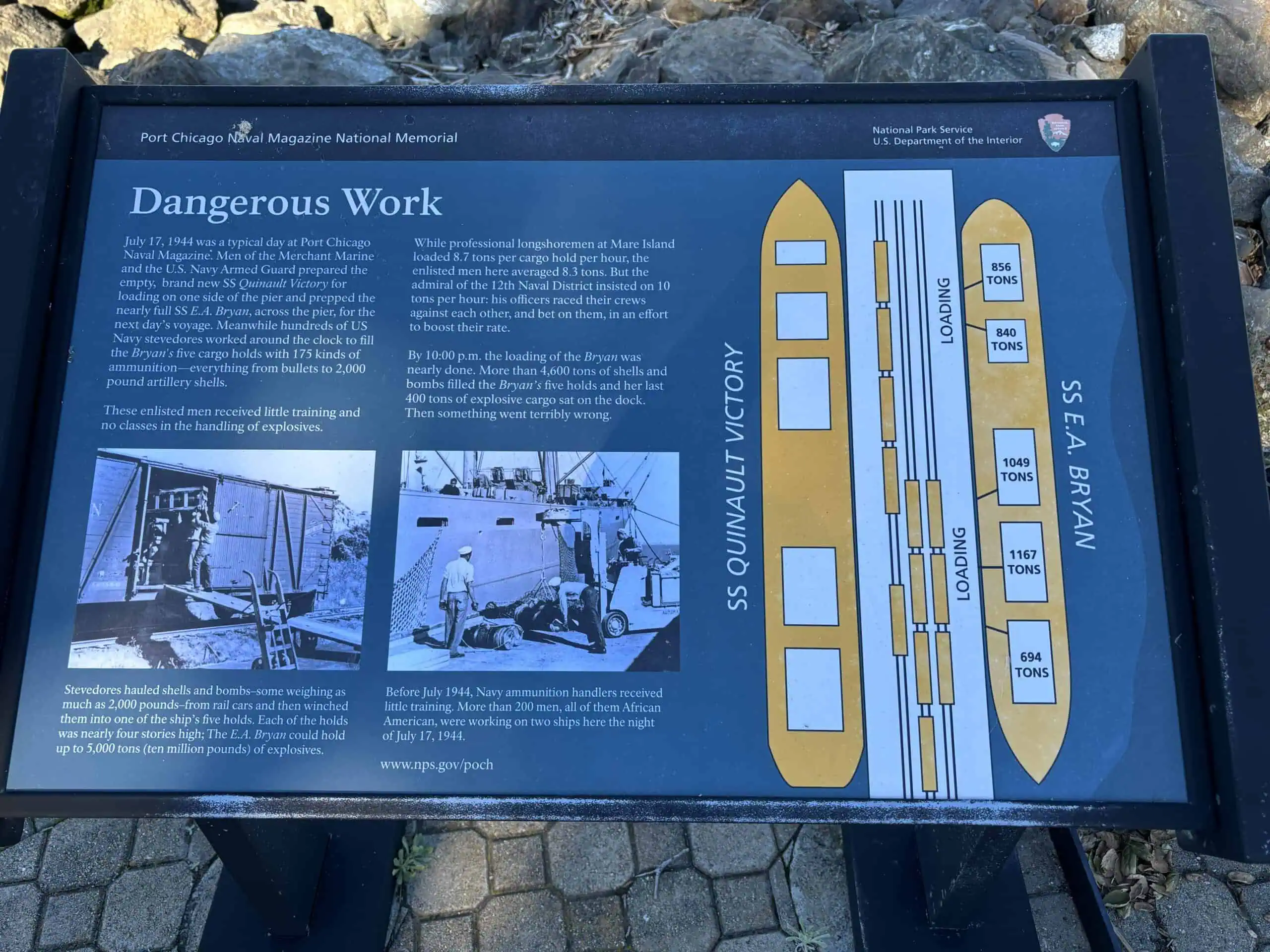

Port Chicago, named after the Windy City due to the near-constant breeze, was a site of immense importance for the military. All munitions needed for the Pacific theater passed through this port before distribution to various war sites, and shipments were needed with urgency and haste. The Navy knowingly denied appropriate training of safe munitions handling for the Black sailors serving there, arguing that the men were incapable of being trained, and they lied that the munitions were not live. Teams of sailors were pitted against one another in deadly races to load ships the fastest, and often faced repercussions of lost wages or time off should they not meet unrealistic expectations. Senior (white) commanders even placed bets among themselves as to which teams would load the ships the fastest.

Defying Coast Guard safety regulations—and in spite of recent warnings from the Coast Guard notifying the Navy of the infractions—the Navy had two ships docked on the fateful night of July 17, 1944. While no one knows exactly what happened to initiate the disaster, two explosions in rapid succession destroyed the two cargo ships, instantly taking the lives of 320 sailors and civilians and injuring at least 390 others. The explosion was so intense, it registered in San Francisco as a 3.2 earthquake on the Richter scale, blasted debris two miles into the air, and caused severe damage to the nearby bunkers and military buildings on site. The death of 202 Black enlisted men accounted for 15% of all Black casualties during World War II.

The aftermath of the disaster—the deadliest home-front military accident of World War II—left a lasting impression not only on the lives affected, but on the annals of U.S. military history. Just three weeks after the catastrophe, the surviving sailors at Port Chicago (those who were not actively on shift at the time of the explosions), were ordered back to work. Demanding training, 256 men declined to load ammunition until training was provided and safety measures were put in place (they agreed to follow any and all other orders). Those men were threatened with charges of mutiny. After coercion and threats, 50 men held their ground.

These men, known now as the “Port Chicago 50” were charged with mutiny in September 1944. The trial was swift, short and predictable—all were found guilty of mutiny, sentenced to 15 years of hard labor followed by dishonorable discharge from the Navy. Review of the practices at Port Chicago did lead to changes within the military, and acknowledgement of racial inequalities ingrained in practice. The disaster and its aftermath also helped lead to the eventual desegregation of the military, with the Navy being the first branch to integrate. However, the verdict of the trial and shame carried by those men stood for decades.

In the 1990s, petitions for exoneration were made to Congress. In 1999, President Bill Clinton offered a pardon, though only one was accepted, as pardons were seen as admission of guilt. It was not until July 2024—eighty years after the disaster—that the US Navy officially exonerated all 256 men, including the Port Chicago 50, and the Navy admitted to egregious errors in training, judgement and representation of the enlisted.

Port Chicago Naval Magazine National Memorial stands today as a quiet reminder of the cost of injustice and of the courage of those who demanded better. Initially established in 1994 by the Navy, it transitioned hands into the National Park Service in 2008. Because the memorial sits on an active Army base, visiting requires advance planning and tenacity: tours are limited, require reservations, and can be cancelled at any time. Tours depart from nearby John Muir National Historic Site in Martinez, where visitors can explore Muir’s home, wander former orchard lands, hike Mount Wanda, and learn about the Juan Bautista de Anza Trail.

The area around Martinez is also rich in other American history: a short drive will take you to Richmond and the Rosie the Riveter WWII Home Front NHP, or to a tour of the author’s home at the Eugene O’Neill NHS. All of these sites are an easy day trip from San Francisco, which is also flush with NPS sites and history. Together they offer a powerful look at the many layers of American history preserved across northern California.

Top photo: African American sailors of an ordnance battalion preparing 5-inch shells for packing, Port Chicago Naval Magazine in 1943 (U.S. Navy)

Sheryl Kepping is an Emergency Medicine Veterinarian in Boise, Idaho. For the past ten years, Sheryl Kepping has been steadily working her way through the more than 420 National Park Service sites—she’s at almost 400 to date. Her mom, Janet, has joined her on many of the trips.