A young filmmaker sets out on a 10,000-mile exploration of the national parks with his childhood best friend during the centennial of the National Park Service. Along the way, the two record stories of people who work in parks and those who come to enjoy them. His stunning film, Out There: A National Parks Story is a tribute to the national parks, their history and the people who work to maintain their beauty.

I’m here with Brendan Hall, adventurer, filmmaker, National Park fan, and believe it or not, civilian astronaut! But we’ll get into that later. Brendan, thanks for taking the time to chat with us.

Yeah, it’s good to be here and good to talk to you guys.

Let’s start with a summary bio challenge. In three sentences, tell us your origin story. How did you grow up? How did you find your way, and what are you doing now?

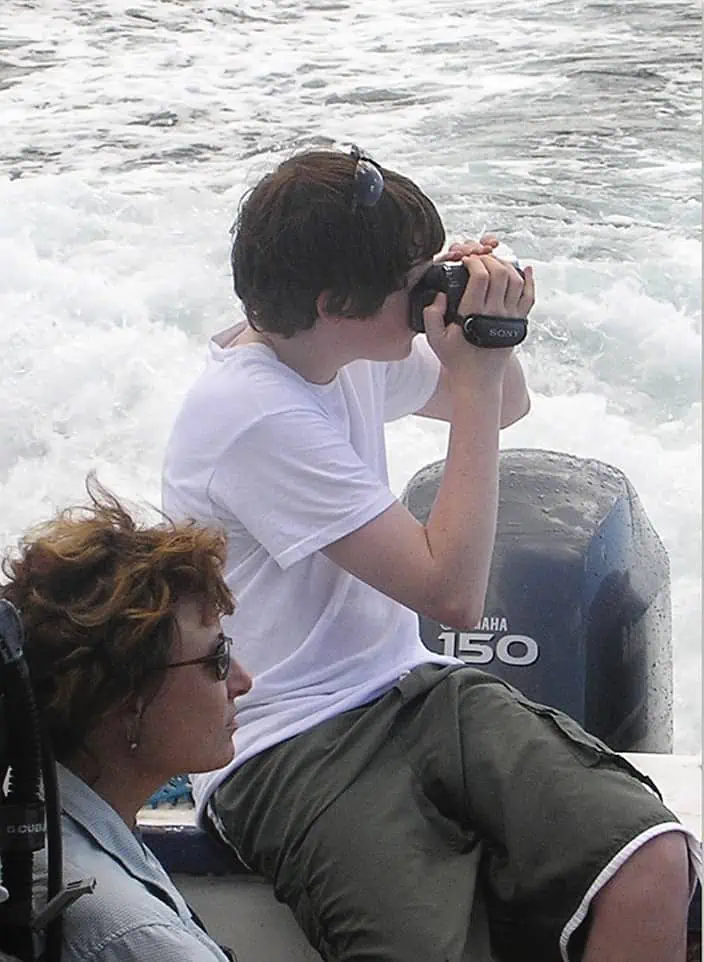

I love that, three sentences. Okay. I grew up in the suburbs of Connecticut, on a small lake with parents who are psychologists and very focused on mental health and empathy, and connecting with people. I found my way because I got a camcorder when I was 12 with some birthday money, and I fell in love with filmmaking, which led me to film school, and then through road tripping led me to loving national parks and nature. And so today I’m a documentary filmmaker. I make films based around nature and exploration, and especially human connection to the natural world, including national parks. It will soon include space. I’ve been very lucky to travel all around the world telling stories for brands and non-profits, and going to some very wild places.

So what was the first park experience that lit the fuse for you? You mentioned you picked up a camcorder and became interested in filmmaking, but what is your first park memory or the one that really impacted you?

In the middle of college I took a road trip with my friend Anthony Blake that was very transformative for my life. I had spent the summer interning in Los Angeles for a couple of Hollywood film studios, and I thought that was kind of the beginning of the rest of my career. I had always wanted to do narrative and Hollywood films. And then, road-tripping back across the country to the East Coast, we went through seven national parks in six days.

I wouldn’t recommend that pace for most people, but at that age, and just the excitement of seeing national parks for the first time, it was completely eye-opening. For me, it was the Grand Canyon that really changed the course of my life, where I was taking photos for the first time. We were watching a sunset that turned into the Milky Way streaming through the sky. I didn’t know it at the time, but it was the Perseid Meteor shower. There were shooting stars through the Milky Way, and then a lightning storm in the distance.

I just thought, this is magic. It made me want to—at least in my twenties—create documentaries rather than narrative Hollywood films, which was a huge departure. I had always kind of pinned my success on trying to be like a Steven Spielberg or a Scorsese, and being in those natural places in these parks changed all of that. It made me want to tell stories of people connecting to these places, kind of like I had. I also wanted to tell a story about the accessibility of these places, because we were just some kids at a viewpoint. We hadn’t hiked to an incredible place. We weren’t some specialty film crew or extreme athletes. We were just a couple of friends who watched a long sunset, and that was enough to change my life. It made me want to tell stories like that for a living.

A nice segue to the film you have on the festival circuit right now, “Out There.” Tell us a little bit about that film and the inspiration for it.

After college—a couple of years after the Grand Canyon experience—I took out a loan and got my first documentary cinema camera and began freelancing. But I was also interning, and then eventually kind of glorified interning in a small role for the National Geographic Channel. In some ways it was what I’d always dreamed of. I was around these amazing and passionate storytellers. I was a part of content that was going on television and around the world. But I was still in an office setting.

So I began dreaming up the most challenging and exciting and meaningful passion project I could possibly create. I also wanted a chance to show my artistic voice and figure out ways I wanted to tell stories—what is that story that only Brendan could tell, based on my life experience, based on my film style. I ended up moving on from Nat Geo and spending a whole summer road-tripping through national parks with my friend Anthony. Our dream behind the project was to create some sort of long-form film showing human connection with the national parks. We ended up spending seven years making this film, my first feature-length documentary.

It’s called Out There: A National Parks Story, and it follows Anthony and me on a 10,000 mile road trip through 20 national parks, east to west across the country, all to meet people in those parks and tell their stories.

The film tells the story of a trail builder in Acadia who’s been there since the 70s; a Native American speaker and artist in Glacier; a female solo backpacker in the Redwoods; and then a French Vietnamese photographer in Yosemite, alongside a lot of other voices. Our dream was to create a sweeping and huge national parks film that communicates that odd wonder you have when you’re in those places. It was almost like when you see someone react to seeing Yosemite for the first time, that look in their eyes. How do you take that and make it into a feature length film? We thought that just seeing the passion and connection to parks in the stories of common people like us—who had just fallen in love with these places—would be something really special. The film came out last year and has been seen in the festival world. This year we’re going to tour it across the country and find a home where it can be seen more widely.

It’s fantastic. A lot of road trip films have a sort of obvious arc where you’re going from here to there. But what was really interesting, I thought, is that you’re also learning about yourself. You’re learning about national parks, and it seems like there was a broadening of your perspective as you moved across the country. Talk a little bit about that and the takeaways for you.

There was definitely a big shift in our perspective. When we set out, we just wanted to see landscapes and explore beautiful places and hit all the trails and see every viewpoint in every park. I think the adrenaline of a road trip and just trying to chase as many places as we could was most important—my first national park road trip included seven parks in six days. So when I originally hit the road to make a film about them, I was thinking of quantity over quality, and I definitely wasn’t thinking of rich and patient human stories.

The first big shift was the understanding that these parks are about people as well. Connecting with people and actually asking questions and learning about these places through perspectives different from my own was one of the most special ways to appreciate them. That was a big one for me.

Another thing I learned is that the creation of art in nature—any kind of long-form art project—sometimes takes a lot longer than you think, and sometimes it goes a lot quicker than you think. I ended up spending seven years creating this project. If you had told me that in 2016, I would have keeled over. I would have said, “No, this is gonna be done next year.” It’s been my New Year’s resolution for the past three years to get the film done. But we were very lucky that the final scene of our film, which ties the entire thing together, was filmed in year six, right at the end of the process. It was a testament for me to just keep faith in the idea that some things take more time than you expect.

Another little piece of wisdom we learned—time and again in the parks—was that having one really meaningful experience is better than trying to see everything. Every time we took that one really great hike and really savored and took our time, it was a much better way to connect to that kind of landscape than trying to hit every viewpoint and scrambling and getting nervous that we’d miss everything.

It’s great advice, actually, for anybody who’s planning a park trip and trying to tick off every box. I hope it’s not a spoiler, but one of the great human moments in the film is when you realize you were not the first member of your family to experience parks in this way. Talk a little bit about your grandfather, and what that meant to you.

I had been traveling the parks for years. At this point we’re going on year four, year five, year six making the film and going further and wider to deeper parks and more people. I took a sightseeing flight over Denali, filming the top of Denali, which was amazing and such a life experience. But I was beginning to wonder when this whole process would end and when I’d finally feel like I had captured the park system. And by pure coincidence I was driving home from New River Gorge National Park after filming with QT Luong, who is a subject in the film and I stopped at my grandparents’ house. I had my camera gear with me and my girlfriend, who’s a filmmaker, was also with me. So we sat my grandfather down—he was 94 at the time. I wanted to hear stories about his adventures, because he had talked about road tripping in the past.

As I talked to him, I realized through his photo album he had taken a trip to Alaska with a friend of his at the same age Anthony and I did our national parks journey. He had not only driven to Alaska, but he had gone to five of the same national parks we had. When you look at the photos, it was like side by side, the same trip—the images in there were a mirror image of mine. And what was so astounding to me was that, first of all, he had paved the way for that trip 70 years before we had. I thought we’d done something unique and adventurous and exciting. But what’s so cool is that I’ve been traveling the parks for years, trying to figure out what the ending of the story was and what the meaning was, and it had been sitting in my grandfather’s living room that whole time.

It was for me an embodiment of this idea of preservation, that the whole park system was founded on balancing enjoyment and protection of these landscapes, and the value of keeping them looking the same and keeping them preserved for almost a century. I mean 70 years, and my grandfather and I looked at the exact same sights and ecosystems. It was a moment that will impact me my entire life, I think, to have such a tangible connection to the past like that. When we first set out to make our film, it was on the centennial of the Park Service—celebrating 100 years. For that to be an ending to it all, I can’t put into words how grateful I am and how much it impacted me. And it’s impacting audiences, too, which is really cool. Everyone gasps when they see the photos side by side.

Yeah, it’s pretty amazing. Let’s have a practical gearhead moment for a minute. Obviously, there are a lot of people who love to film video and take photographs in parks. What did you use to make the film, and any tips for young photographers and filmmakers?

Something we got lucky with is, I had a Canon C300 Mark II documentary cinema camera when we started filming in 2016. For filmmakers who don’t know, that’s still actually a really great documentary camera. It shoots 4K, with a really nice log color profile and amazing dynamic range. The benefit of that was that through a seven-year filmmaking process, the quality of the image still feels really good and cohesive. We could continue to film and kind of intercut some modern and some past stuff, and it still looked really good. So that was our main camera.

We often shot with the gimbal, which was hugely important. It was kind of like an original Ronin gimbal, which is bigger. Nowadays you can get them a lot smaller, which is cool and would have been helpful for us, because I would be hiking this 15-pound camera rig on trails, and any time you see a shot moving up a tree is me physically pushing the camera up. Along with the gimbal, we used a handheld camera, and both a lightweight photo tripod for longer hikes as well as a sturdy or heavy-duty tripod for long lens stuff in the parks.

Some of the time lapses were shot real time. We’d shoot 15-20 minutes of the clouds moving. Without the jittery trees and cars it looks really nice, because it’s through your cinema camera, which for me just has this look. But we shot a lot of time lapses, on a DSLR as well. So you’re firing off single frames, using an intervalometer setting every 2, 3, 4 seconds. For night lapses it’s every 30 seconds because you’re shooting 20- or 30-second long exposures. We spent a lot of nights sleeping on camping pads for two hours, three hours while the camera moved across the night skies. So a lot of gear.

That’s fun stuff. Okay. So just stepping back to the big picture again. I mean, obviously, you went to a lot of parks in the making of the film and your previous road trips. I’m just curious what your park number stands at right now. A lot of people try to get to all 63 of the major national parks, and of course there are 428 national park sites. Are you keeping count? And do you know how many you’ve visited?

I don’t have my National Park Service sites number. I know that in my lifetime I’m around 46 national parks. I’m 29 now, so the accumulation of that happened very quickly. But now I’m really taking my time being patient, and I’m not rushing anymore to tick them all off. I would like to do it in my lifetime. But I got my fill of a lot of parks very quickly, so I’m excited to take them one at a time.

Any favorites so far?

Man, so many, I mean, what’s so cool is that each park protects a unique ecosystem. For me, my emotional side, I get excited by different parts of each ecosystem in nature. They’re almost like different friends to me or different personalities. It’s also all about the people you go with—you can go to a mediocre place in nature with the best people and have a way better time than a very iconic place with the wrong people, or in a tough state of mind. It’s so subjective what experience you have.

I really love Glacier National Park. It is just stunning and it has all the big features of a national park, in terms of wildlife and landscapes. There are mountains and lakes and grassy meadows, and grizzly bears and goats, even long-horned goats. That part is just amazing. Then also, I think it represents the positives and negatives in other ways, too, where you see evidence of climate change right in your face. There used to be over a hundred glaciers, and now I think there are 30 or less—you can see the side-by-side photos of them disappearing.

Then also the Native American heritage and history there. The Blackfeet Reservation is next to the park. And that heritage is still alive and well, and being told very beautifully by Blackfeet storytellers. But it’s also a story of displacement and being pushed off some of that land for the park to be created. I love Glacier for that sense that it’s a mixture of history and an important American legacy to try to understand—both the positive and the darker sides. And it’s just a stunning place to go. In terms of what makes a national park a national park, all that stuff is really rich there.

Yeah, absolutely. So we know that when you’re going into nature, there’s always going to be surprises. I’m curious, what was your biggest park fail?

A big one was when we only had a day and a half in Grand Teton National Park, which was way too short, and it was just dumping rain the entire time. We were able to film just one sunset that broke through the rain and the clouds. But we’d also not really planned well. People told us it would get really cold at night. We were young—we were 22—and just like, oh, but it’s summer, how cold could it get? Anthony only had tank tops with him. I was the only one who had a rain jacket. I had accidentally left both my sleeping bag and my pillow at other parks, in motels.

So we got there, we were camping, and we were freezing, and it was raining, and from a filming perspective we were just under-prepared. It was a total mess. I think we have plenty of moments like that where we were just learning camping as we went. That wasn’t something either of us were used to, and so we were dropping camping stoves and ripping stuff, and messing up how we built things. We were hiking with backpacks that were too heavy. I would say it was a constant stumble and bumble.

Okay, well, in the course of the seven years of making this film, you also learned at one point that you had been selected for an unbelievable experience. Can you tell us about that?

Yeah. So early in 2021, I saw a news article saying that a Japanese billionaire, an entrepreneur named Yusaku Maezawa, was taking eight artisan creatives on a journey with him around the moon. And I was like, that is just too impossible to believe. So I read more. And what’s crazy is, I could have done anything differently with my day or my life before that moment, and I might never have seen this news article. He had purchased the first-ever seats aboard a Space X rocket called Starship that’s being developed for larger crews and deep space travel to the moon and Mars. His dream is to bring eight artists and creatives from around the world.

We’ve seen astronauts go into space, some of whom created art. But we’ve also seen scientists, and a very traditional kind of person. What if we brought artists and creatives? What would they create and how would they feel, and how would they translate the experience into some kind of medium. I applied on a whim and submitted a little video application and some written prompts, and then that eventually kicked off a year-long process of interviews, a psychological interview, a medical exam, eventually a big-group, in-person interview. At the end of that year, I had a call with MZ the entrepreneur, and he said, “I just want to ask you a few more questions about your application.” So I hopped on Zoom, and he asked, “Do you want to know the moon crew announcement and who was selected?” I said, “Sure,” and that was kind of my “American Idol” moment when I knew that my life would inevitably change one way or the other. And he said, “I’d love you to join the mission and be a crew member.”

So I’m a member of the dearMoon project. There are eight of us from around the world, and I’ll be in the documentary filmmaker role. There are a couple of photographers; there’s a YouTube educator, a choreographer, an actor, a famous DJ and K-Pop star. We’re an eccentric, passionate group that’s eventually gonna go around the moon sometime in the coming years.

It’s a surreal and incredible project that I’m just beyond grateful for. What excites me is that so much of what I learned in national parks can be applied to this in terms of the wonder and human connection with the natural world, and that this is really a human story that we’re telling. It’s not just the Earth. It’s not just the moon. It’s our connection to them. It’s also about the idea of preservation. You know, space is this whole other place to balance enjoyment and preservation—the same way the park system does.

I attribute this space journey to this passion project, my film “Out There.” It just blows my mind that if I had never left after college and taken this road trip, or even gone to the Grand Canyon once in the middle of college, I never would have created this film, connected with my grandfather in that way, or eventually gone to space. It’s just this really cool testament, for me, to just chase what you’re passionate about and get a little bit out of your comfort zone, because you just never know where that first park or that first place is going to take you.

So 300 million people are visiting national parks every year. There’s a massive surge right now, post pandemic. People are getting out there, but visitation is older and less diverse than it should be. What do you say to people who have been reluctant so far to get out there?

I think the first thing is just to form a genuine connection with nature. That can begin with a city park, a state park somewhere, but closer to you, and then eventually get out to a national park—especially one that’s just totally different than you’ve ever experienced.

If you have the means and you have the ability to go, it’s absolutely worth it to do so, and especially at a young age, too. There are a lot of folks who wait till they retire to first see the park system, which I completely understand, because you’re working and you’re busy, and you have other obligations. But if you’re able, I think you’ll find some of your best personal growth. Push your limits and get outside your comfort zone.

What we learned, and the reason we called the film “Out There”—it’s not a super national park-y title—but we really believe that some of the best things in life exist outside your comfort zone. We were shown that time and time again through all these stories of the people we’ve met. I think that was the through line of the whole thing, that when you push your comfort just a little bit and get out to a new place that you might be excited but unsure about, the rest will figure itself out and you’ll have a really amazing experience.

I’d also say, for people who have significant means, to support others’ journeys in the parks. More than ever I think we need to make these places accessible. Support organizations that are bringing people out to these places that they might never have access to, and kind of let everyone come along for the ride. In theory the parks are open to everyone, and it’s such a beautiful idea, so important. But in practice not everyone has the accessibility, whether it’s financial means or just the confidence and encouragement that someone like them has a place in the outdoors. The more we can support that as a community, I think, the healthier the park system will be.

What I’d say is, go out and explore, however you’re comfortable-–but also know that outside your comfort zone is some of the coolest stuff. Talking to people, talking to rangers, talking to someone you might never expect to have a conversation with, can lead to a really beautiful interaction.

Okay, well it may be a couple of years yet before you go off to the moon. So in the meantime, what is your next adventure? Have you plotted it out yet?

I haven’t plotted my next big adventure. I want to make a film about oceans because I’m a scuba diver. I think that oceans are the next big ecosystem that is being threatened; coral reefs are disappearing, and that’s all just happening in real time. I’d really like to make a film to help preserve oceans, and highlight that human connection which I think we’ve seen a little bit less of.

We’re also planning a big cross country tour with “Out There,” in late summer, fingers crossed. We want to take the film east to west across the country, hit cities, hit national parks, every kind of community venue you can think of, and use the film as a conduit to share an awesome evening with people reflecting on the spaces, having talks. We’re going to pair live music with it. So my next journey, I hope, is actually going across the country again, but this time being able to share this and connect with people in a whole different way.

Fantastic. Everybody should see it. It’s an inspiring film, and it’s beautifully made. Thanks again for taking the time to chat with us.

My pleasure. I love the Parks Channel, so I’m here for it.

To meet one of the people Brendan filmed on his journey, check out this video produced and edited by Isabel Shelkin.