Five Classic Hikes in Great Smoky Mountains NP

An iconic mountain summit, a peaceful waterfall, panoramic vistas. Whatever you're seeking, the Smokies offer a wide range of hiking opportunities, from easy walks to challenging climbs. Here are five great hikes in Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

With stunning views, diverse landscapes, and opportunities for both relaxation and adventure, Great Smoky Mountains is one of the most beloved national parks in the U.S. Before you head out, though, here are some tips:

- Because some of these trails are so popular and can become crowded with limited parking, we list some alternative hikes as well.

- The park does not charge an entrance fee, but all vehicles parking for longer than 15 minutes anywhere in the park are required to have a parking tag. Many of the trailheads have very limited parking so consider taking a shuttle and avoiding the stress.

- Bring (or download) a map as GPS may not be accurate in the mountains.

- Don’t bring your dog, as they are not welcome on any of the trails.

- Always check the NPS website for the latest conditions and closures.

And now, here are five great hikes in Great Smoky Mountains NP:

1. Alum Cave Trail

One of the park’s most popular hikes, the Alum Cave Trail offers a perfect mix of natural beauty and geological wonder. The trail climbs through lush forests and past rocky outcroppings before reaching the dramatic Alum Cave Bluffs. These towering white sandstone bluffs offer stunning views of the surrounding mountains. The trail also passes through Arch Rock, a natural rock arch, and provides glimpses of the park’s diverse ecosystems. It’s a rewarding hike that’s moderately challenging and perfect for those looking for a mix of adventure and scenic views.

Distance: 4.6 miles (round-trip)

Difficulty: Moderate

Elevation Gain: 1,125 feet

Alternative hike: Andrews Bald

2. Grotto Falls Trail

For a shorter, family-friendly trail that leads to a beautiful waterfall, the Grotto Falls Trail is a fantastic choice. This easy-to-moderate trail meanders through a peaceful forest and brings you to Grotto Falls, a 25-foot waterfall that you can actually walk behind! It’s one of the few waterfalls in the Smokies where you can get up close and personal with the flowing water. The trail is particularly picturesque in spring when wildflowers bloom along the path, and the waterfall is especially captivating after rain.

Distance: 2.6 miles (Round-trip)

Difficulty: Moderate

Elevation Gain: 600 feet

Alternative hike: Baskins Creek Falls

The Charlies Bunion Trail is one of the best hikes for panoramic mountain views. This trail follows a section of the Appalachian Trail and climbs through the lush forests of the Smokies before reaching Charlies Bunion, a rocky outcrop offering 360-degree views of the surrounding mountains and valleys. The trail is moderately strenuous, with a steady climb and some rocky terrain, but the views at the end are well worth the effort. On clear days, you can see deep into Tennessee and North Carolina, making this a favorite for photographers and hikers alike.

Difficulty: Moderate

Distance: 8 miles (Round-trip)

Elevation Gain: 1,700 feet

Alternate hike: Chimney Tops Overlook

For a more challenging hike, the Mount LeConte Trail is a must for experienced hikers. At 10 miles (16.1 km) roundtrip, this is the shortest of the five routes to Mount LeConte, one of the highest peaks in the Smokies. It’s a strenuous adventure, but the views from the summit make it one of the park’s most rewarding hikes. The trail ascends through dense forests, past wildflower-filled meadows, and over rocky outcrops. At the top, hikers are rewarded with panoramic views and the chance to visit LeConte Lodge, the highest lodge in the park, where you can rest and take in the mountain scenery. This trail is tough but offers a truly unforgettable experience.

Difficulty: Difficult

Distance: 10 miles (Round-trip)

Elevation Gain: 2,700 feet

Alternative hikes: Appalachian Trail & Boulevard Trail to Mount LeConte (16.2 miles roundtrip); Bullhead Trail to Mount LeConte (13.6 miles roundtrip); Trillium Gap Trail to Mount LeConte (13 miles roundtrip); Rainbow Falls Trail to Mount LeConte (13 miles roundtrip)

Kuwohi—formerly known as Clingmans Dome, and recently restored to its native American name—is deeply significant in Cherokee culture and a place of spiritual importance. In Cherokee syllabary, the name is ᎫᏬᎯ and means “mulberry place”. As the highest point in the park, Kuwohi offers breathtaking views. The paved trail is 0.5 miles each way—steep but rewarding—and leads to an observation tower with stunning 360-degree vistas. In winter, road closures add a 7-mile hike, but snowy landscapes and crystal-clear skies make the journey worthwhile. Whether you’re visiting for the views or its rich history, this iconic destination leaves a lasting impression year-round.

Distance: 0.5 miles in summer; 7 miles in winter

Difficulty: strenuous

Elevation gain: 330 feet in summer; 1,200 feet in winter

Alternative: There is nothing like it!

Top photo by Freedom Naruk/Freepik

Top 10 Things to do at Indiana Dunes NP

An hour's drive from Chicago, it's a haven for nature lovers, adventurers, and families. Spanning 15,000 acres along the southern shore of Lake Michigan, the park is home to diverse ecosystems, rich history and fun for all ages. Here are the top 10 things to do at Indiana Dunes National Park.

1. Hike the Dunes

Explore the towering dunes that define the park. Trails like the Dune Succession Trail at West Beach offer spectacular views of Lake Michigan after a challenging ascent. Arrive early to secure a spot, especially on weekends. For real-time information on parking availability, check the Congestion Monitor.

2. Explore the Trails

Explore beyond the sand dunes on 15 unique trail systems that span over 50 miles, each offering its own adventure. From short easy strolls to challenging all-day treks, most of the trails are open all year and the hiking experience will change with each season. The Cowles Bog Trail, named after ecological pioneer Henry Chandler Cowles, takes you through wetlands, forests, and dunes, offering a mix of scenery and wildlife.

3. Relax on the Beaches

Indiana Dunes boasts some of the best beaches in the Midwest. West Beach and Porter Beach are popular spots for swimming, sunbathing, and picnicking. West Beach has a large parking lot with facilities, while parking at Porter Beach is more limited. Arrive early (or late) in peak summer months to avoid crowds. Don’t miss the sunsets over Lake Michigan—they’re breathtaking!

4. Birdwatching

The park is a premier destination for birdwatchers, with over 350 recorded species. During migration seasons, you can spot hawks, sandhill cranes, warblers, and waterfowl. The Indiana Dunes Birding Festival, held during the third weekend of May is a remarkable four-day event highlighting dozens of birding hotspots across the region with guided outings led by experts. Registration opens March 1.

5. Camp Under the Stars

Stay at one of the campgrounds for a night immersed in nature. Three campgrounds offer a mix of sites, including RV and tent accommodations, providing a serene setting near the park’s main attractions. Dunewood Campground, the park’s main site, features 66 campsites with modern amenities, including restrooms and showers. Reservations are available six months in advance at Recreation.gov.

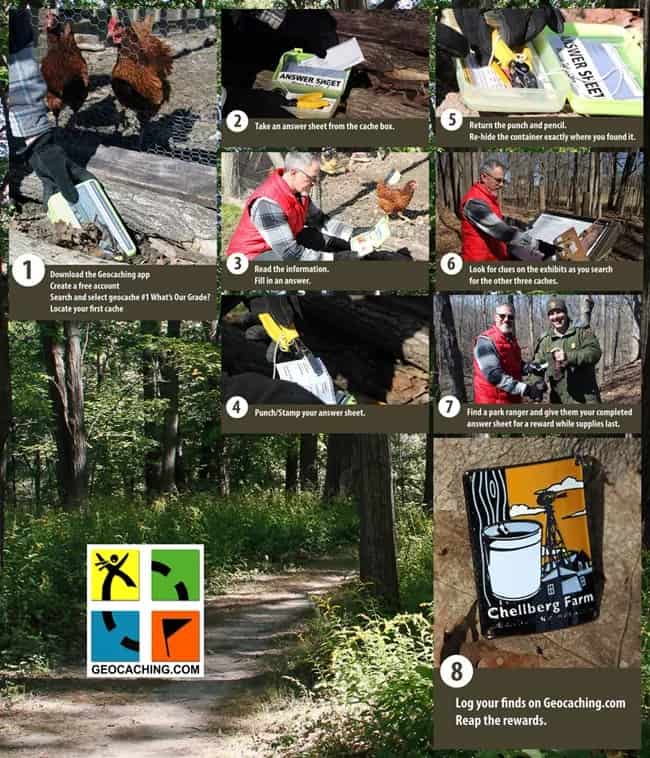

6. Geocaching

This modern-day treasure hunt combines technology with outdoor adventure, making it a great activity for families, friends, and solo explorers. Indiana Dunes has four unique types of geochaches: Traditional, EarthCaches, Lab Geocaches and Virtual Caches. Register for a free account and visit NPS.gov for more information.

7. Diana Dunes Dare

The Diana Dunes Dare is an inspiring trail challenge celebrating Alice Mabel Gray, nicknamed “Diana of the Dunes.” This self-guided hike honors Gray’s legacy as a naturalist and conservationist who lived along the dunes in the early 1900s. Follow scenic trails and explore diverse landscapes like towering dunes, wetlands, and beaches. Complete the challenge for a commemorative sticker. Best of all, pets on leashes are allowed!

8. Kayaking and Canoeing

Paddle along the Little Calumet River or the shoreline of Lake Michigan. These waterways offer calm stretches for beginners and scenic views of the surrounding landscapes. Always check the weather and water conditions, know your limits, and remember, swimmers always come first.

9. Century of Progress Homes

Indiana Dunes preserves more than 60 historic structures, including the Bailly Homestead, a National Historic Landmark. Other notable sites include Camp Good Fellow, Chellberg Farm, and five iconic houses from the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair. The Century of Progress Homes showcase innovative architecture from the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair. These five modernist houses highlight cutting-edge materials and designs of the era and focus on futuristic living and sustainability.

View this post on Instagram

A post shared by Devon & Mitch | Our Florida Passport (@ourfloridapassport)

10. Biking

Indiana Dunes offers more than 37 miles of trails, weaving through forests, wetlands, prairies, and along the stunning Lake Michigan shoreline. The scenic Calumet Trail and the Dune Ridge Trail are favorites, with breathtaking views and varying terrains.

Top photo of Mount Baldy, the largest “living” dune in Indiana Dunes National Park by Christine Livingston CC BY-SA 4.0

Van Cortlandt Park, A Hidden Gem in the Bronx

It’s my fourth year as a New Yorker, and I am finally coming around to the idea that you don’t have to travel far—or even leave the city—to get a good dose of open green space. Van Cortlandt Park is a hidden gem right in the Bronx.

Maybe I’ve been too stubborn. Having grown up in a small Connecticut town, I was spoiled by the two acres of woods in our backyard, the creek with its footbridge down the street, and the hiking trail at the end of our driveway. I figured, then, that nature must be sought outside the five boroughs, with a couple-hour drive upstate or across state lines. But New York City, I’ve come to learn, has more to offer in the way of parks than a patch of grass and a swing set (which, don’t get me wrong, are necessary in their own right).

This sentiment was at the forefront of my mind when my friend suggested we spend a late-October Sunday in Central Park, basking in the autumn foliage. Central Park is beautiful, of course, but I had my sights set elsewhere. Gently, I countered: how about we take a trip to the Bronx? Had he heard of Van Cortlandt Park?

My interest in Van Cortlandt Park was manifold. First, I am a city-dweller who loves the outdoors and greatly misses the woods of her hometown. Second, I am drawn to places with compelling histories—and Van Cortlandt Park has that, in abundance. And, finally, I am ever-curious about so-called hidden gems. The park had been on my radar for some time.

Located in the northwest Bronx and spanning an impressive 1,146 acres, Van Cortlandt Park is New York City’s third largest park. The first and second largest parks are Pelham Bay Park (2,765 acres) and Staten Island’s Greenbelt (1,778 acres), respectively. Central Park sits in fifth place at 843 acres.

Beyond its impressive acreage and expected attractions (athletic fields, two miles of shaded hiking trails, etc.), Van Cortlandt Park boasts a seasonally-open outdoor pool, horseback riding trails, and the oldest public golf course in the United States, to name a few. Plus, there is the Van Cortlandt House Museum, the nature center, and an abundance of events and programs offered by the Van Cortlandt Park Alliance. I was thrilled when my “let’s visit the Bronx” suggestion was met with enthusiasm.

Van Cortlandt Park: A Brief History

Of course, the land comprising Van Cortlandt Park existed long before it became a public park. It existed long before the Van Cortlandts, a wealthy and politically influential family of Dutch origin, owned the land from the late 17th century through the end of the 19th century.

The park’s natural topography—its distinct ridges, hillsides, and flats—were formed twenty-thousand years ago when the glaciers that covered what is now New York receded. Another seven-thousand years passed before Indigenous Americans came to the area, and by 1000 AD the Lenape had built permanent settlements there. They lived on the land until 1639, when the Dutch East India Company brought the first Europeans to settle the Bronx.

To summarize a complicated history, Jacobus Van Cortlandt, a wealthy merchant and two-time New York City mayor, acquired the land in 1864. Jacobus and his descendants owned the land for generations, largely as a working plantation where they enslaved Africans and a number of Indigenous people. In 1888, with the help of the New York Parks Association, the City of New York acquired an unprecedented 4,000 acres of parkland in the Bronx, including what would, in 1913, officially be named Van Cortlandt Park.

As my visit would soon reveal, the often-fraught history of the land is on full display. Informational plaques, part of NYC Park’s Historical Signs Project, are placed throughout the park, educating parkgoers on the historical significance of what might otherwise be mistaken for a miscellaneous plot of land or a random stone. Among efforts to reclaim and recontextualize history, the Enslaved People Project is engaged in several initiatives to educate the public, including developing educational material and running community workshops.

Visiting Van Cortlandt

The day of the park trip arrived. I had read up on some of the park history, and knew I wanted to tour the historic house and walk some of the hiking trails. But beyond that, planning was minimal. I figured I would show up and see what enticed me.

My friend and I traveled by car, a 35-minute drive from North Brooklyn, and easily found a parking spot in the free lot by the Van Cortlandt Golf Course. New Yorkers who don’t have access to a car don’t need to fret. The park is also accessible by bus and subway.

It was early afternoon when we entered the park. The temperature hung in the mid-fifties, and the sky was blue and almost entirely clear. My first impression: amazement at the expansiveness of the park’s fields. Historically used for agriculture, today the fields are filled with jersey-clad kids kicking soccer balls into goals and park visitors strolling with dogs, pausing to take photos of the trees dotting the fields.

Van Cortlandt House Museum

Our first stop: Van Cortlandt House Museum. The house is made of brick and stone and sits two-stories tall, plus an attic with dormer windows. There is an herb garden, too.

It was built by enslaved Africans in 1748 – 1749, under the supervision of Frederick Van Cortlandt, Jacobus’ son. After the City of New York acquired the land and the house in the late 19th century, the National Society of Colonial Dames restored it, complete with furnishings that showcase what it might have looked like from 1749 – 1820.

The house is open for self-guided tours Wednesday through Sunday, 11 AM through 4 PM, with 3:30 as the latest arrival time. For most adults, admission is $5, although there are exceptions for Bronx residents and children, among others. The day of our visit coincided with an event, Wags to Witches. Fortunately, that meant a lot of costumed dogs wandering around excitedly. Unfortunately, that meant museum staff were preoccupied and the second and third floors of the house were closed for the day.

While I was disappointed to not have full access to the house, the three rooms on the first floor offered a good glimpse into the Van Cortlandt’s home. The light-flooded East Parlor was the most formal room of the house where the Van Cortlandts entertained their most wealthy, elite friends: the Rennsalears, the Delanceys, the Astors, and so on. “All the families who have streets named after them,” my friend remarked.

As a fan of bright colors, I was particularly fond of the West Parlor. Its north wall is painted blue and orange and features a fireplace and built-in cabinets, their doors open to reveal delicate china. As the sign indicates, the blue and orange were actually the original colors of the wall, as revealed by microscopic paint chip analysis—a fascinating glimpse into the restoration process.

The last room we visited was the Dining Room. The area was a bit crowded, making it difficult to get a good photo. (Luckily, the museum website can bridge that gap.) I was particularly fond of the blue wallpaper here and fascinated to learn that it is a reproduction of wallpaper from around 1820, discovered during the restoration process.

While I lamented the fact that I couldn’t climb the stairs to the upper levels, as well as the barriers that kept visitors from wandering freely through the rooms and examining the artifacts up close, the house museum was a unique, educational, and aesthetically interesting introduction to the park, and an experience I wholeheartedly recommend.

Nature Trails

While much of Van Cortlandt Park is comprised of open fields, it boasts a handful of hiking trails, too. We spent most of our time on the Cross Country Trail, veering off to wander smaller trails in the Northwest Forest.

If you’re looking for a challenging hike filled with unrelenting inclines and rugged landscapes, this is not your place. But for a New York City park, the trails surpassed my expectations. They are beautiful and relatively quiet, and we stopped in several spots to admire a uniquely shaped tree branch or climb a fallen trunk. In many parts, the trees grow thick enough and the foot traffic is scarce enough that I forgot I was, in fact, in the Bronx.

The highlight of the hike: the Vault Hill Overlook. We climbed over the rocks and sat for nearly an hour in the sunshine, gazing at the Manhattan skyline, the George Washington Bridge, and the park’s Parade Ground below.

There were a handful of people around, scattered across the rocks. Like everyone else we’d encountered, they were respectful, friendly, and kept to themselves. That was my general impression of the Van Cortlandt parkgoers: they’d offer a nod or a smile and be on their way.

Burial Grounds

As I mentioned, and as the signs throughout the house museum reinforce, the park does not shy away from the truth: the Van Cortlandts were slave owners, and this land was once a plantation. Crucial acknowledgements of the African and Indigenous people who worked, lived, and died on the land are abundant.

One such site is the Enslaved African Burial Ground, which sits not far from the house. In present day, the burial ground is a fenced-in plot of land, filled with trees and covered in leaves. We pause to read the sign and engage in a friendly staring contest with a squirrel, intently munching on an acorn.

There aren’t many people around us; the park feels quiet and still. I am overcome with the strangeness of being in a place so beautiful but whose history is steeped in racial violence. I consider that this is the case for many beautiful places in America, except there aren’t carefully researched signs to point it out.

Researchers discovered the burial ground (where both African and Indigenous people were buried) through the use of primary documents such as wills, land deeds, and estate inventories, as well as accounts from workers who discovered skeletal remains in the 1870s. In 2019, these findings were corroborated by a USDA geophysical study that used ground-penetrating radar.

Notably, this burial ground sits along the eastern edge of the Kingsbridge Burial Ground, where some of the area’s earliest colonial settlers were buried until the early 19th century.

Our third encounter with a burial ground came as we meandered along the Cross Country Trail. This cemetery sits atop Vault Hill and was the burial site of many Van Cortlandt family members until 1888, when the land became a public park. The vault is square, smaller than I’d expect, and made of a tall stone wall and iron fence with an ornate gate, which is locked. The plot is fairly overgrown and, without the signs indicating otherwise, the stone walls might be mistaken for any old abandoned structure.

We pause to read and learn that the grounds were vandalized in the 1960s, and the headstones and markers were removed. I wonder aloud what it looked like before.

It is here that I learn the park’s significance during the Revolutionary War. During a visit to his ailing mother, City Clerk Augustus Van Cortlandt used the family vault to successfully hide city records from the British before they occupied New York. Later, he safely retrieved them.

Later research revealed that George Washington allegedly instructed campfires to be lit on Vault Hill in order to trick the British into believing that the army was still present, when they had actually decamped in Yorktown.

Revolutionary War buffs, I have found the park for you!

Thirteen Stone Pillars

As we walked away from Vault Hill, we ran into three park rangers. Dusk had snuck up on us, and we were quickly running out of sunlight so we asked for their advice. What’s one more place we could swing by, before we drove back to Brooklyn? They were friendly, enthusiastic, and happy to chat. One offered up a suggestion: the Thirteen Stone Pillars. It was a quick walk away, toward the parking lot, and we could make it before the sun set.

The Thirteen Stone Pillars are just that: thirteen stone pillars, standing just off what was once part of the Putnam Branch of the New York Central Railroad and is now a nature trail.

As is the case with the rest of the park, though, these stones have history.

In 1905, the New York Central Railroad placed fifteen stones (thirteen of which remain) on the parkland in order to measure how various granite, limestone, and marble samples would fare during the winter months. Grand Central Terminal was under construction, and the railroad and its architects were deciding what type of stone to use for the exterior curtain wall of the head house. I’ll spoil it for you. The winners were the Indiana limestone (second stone from the left) and the Stony Creek granite (most likely, the third from the right).

We walked among the pillars, running our hands over the cold stone and appreciating how firmly planted in the ground they remained, over a century later.

The sun had almost set by then, and we made our way back to the car and back to Brooklyn.

My Parting Thoughts

I will be visiting Van Cortlandt Park again, and I think you should, too. In particular, the park offers something special to NYC residents in search of wooded trails and open spaces, as well as people who are interested in learning the history of the land on which they walk, run, hike, and even golf or swim.

Next time, I’d like to visit the second and third floors of the Van Cortlandt House Museum. I’d like to stop by the Nature Center and take advantage of a walking tour. I’d like to get to the area early enough to grab breakfast at The Irish Coffee Shop nearby, a recommendation from a friend who grew up in the neighborhood.

In the weeks after my visit, and in the process of writing this, I’ve found myself increasingly reflecting on the complex history of the land in relation to the straightforward beauty I witnessed and joy I experienced during my visit. I have, too, found myself increasingly interested in learning more, so that I might return to the park more knowledgeable. I wonder how that will inform my experience.

A park is a place for recreation, for enjoyment of nature, for stillness and solitude. A park is, too, a place for remembrance, reclamation, and community-building. Sometimes, you find all that in one place, hidden in plain sight, on a thousand acres in the Bronx.

All photos courtesy of the author unless otherwise noted. Top photo vancortlandtlakehouse.com.

Five Best Hikes in Grand Canyon National Park

Breathtaking views and an unforgettable experience, perfect for both seasoned adventurers and those seeking memorable day hikes. Here are the five best hikes in the Grand Canyon, from challenging descents to scenic rim trails.

1. Bright Angel Trail

Bright Angel Trail is one of the most iconic and accessible trails in the park, beginning at the South Rim and descending into the canyon. The trail’s switchbacks and steep inclines demand strong legs and stamina, especially on the return. Hikers are rewarded with incredible views, wildlife sightings, and geological formations that make it worth the effort. Note: there will be mules on this trail.

Distance: 9.5 miles one-way (full hike to the Colorado River)

Difficulty: Difficult

Tips: This well-maintained trail offers several turnaround points, which make it easier to customize based on your fitness level. Start early to avoid the midday heat, as there is limited shade.

Watch tips on how to stay safe while hiking in the Grand Canyon

2. South Kaibab Trail

The South Kaibab Trail offers some of the most dramatic vistas in the park. Unlike the Bright Angel Trail, this trail has very little shade and has no water along the trail, making it more demanding but incredibly rewarding. Hikers are treated to stunning panoramic views throughout, with popular stopping points like Ooh Aah Point and Skeleton Point that offer postcard-perfect views.

Distance: 6 miles round-trip to Skeleton Point

Difficulty: Strenuous

Tips: Due to the trail’s exposure to the sun, pack extra water and sun protection. The views are well worth the effort, so don’t forget your camera!

3. North Kaibab Trail

For those venturing to the North Rim, the North Kaibab Trail is the park’s only maintained trail that descends into the canyon from this side. Known for its solitude and lush surroundings, this trail takes hikers past waterfalls and the stunning rock layers of the Redwall section to Roaring Springs.

Distance: 9.4 miles round-trip to Roaring Springs

Difficulty: Extremely strenuous

Tips: This trail is quieter than those on the South Rim, making it ideal for those seeking a more secluded experience. Begin before 7 a.m. and be prepared for a long, challenging hike.

For a more leisurely experience, the Rim Trail follows the South Rim for about 13 miles, from the South Kaibab Trailhead to Hermits Rest. This mostly paved trail provides incredible views without the intense elevation changes of other canyon trails. Perfect for families or those looking for accessible viewpoints, the Rim Trail offers multiple overlooks, benches, and shuttle stops along the way.

Distance: Up to 13 miles one-way

Difficulty: Easy to moderate

Tips: You can hike as much or as little of the trail as you like, and since much of it is paved, this trail is also wheelchair accessible in certain sections.

For the billy goats out there, the Grandview Trail is a challenging, steep trail that descends about 3 miles (4.8 km) to Horseshoe Mesa, with options to continue further. Originally constructed in 1893 as a mining route, the trail is rocky, exposed, and demands caution. Featuring large steps, rugged terrain, and extreme dropoffs, the trail has an elevation change of around 2,600 feet (792 meters) in those three miles, making it best suited for experienced hikers. NPS recommends hikers not use this trail to access the Colorado River and consider walking the Bright Angel Trail for an easier hike.

Distance: 3 miles one way to Horseshoe Mesa

Difficulty: Extremely difficult, recommended for experienced desert hikers

Tips: Trail conditions can be rough, and it’s less maintained than popular routes like Bright Angel, so sturdy boots are essential. Start early to avoid heat, especially in summer, and carry plenty of water, as there’s little shade and no water along the trail.

Before you set out, always check the NPS website for the latest information and always HIKE SMART. Carry plenty of water and snacks, and although there are some places where pre-treated drinking water is available, make sure you have a method to treat water. And remember to bring The Ten Essentials, a list compiled by Sarah Shier, a Preventative Search and Rescue (PSAR) Ranger at Grand Canyon National Park. Her role is centered on educating hikers about the potential dangers of the trails and helping them plan to avoid incidents that could lead to rescues.

Top photo by EyeEm/Freepik

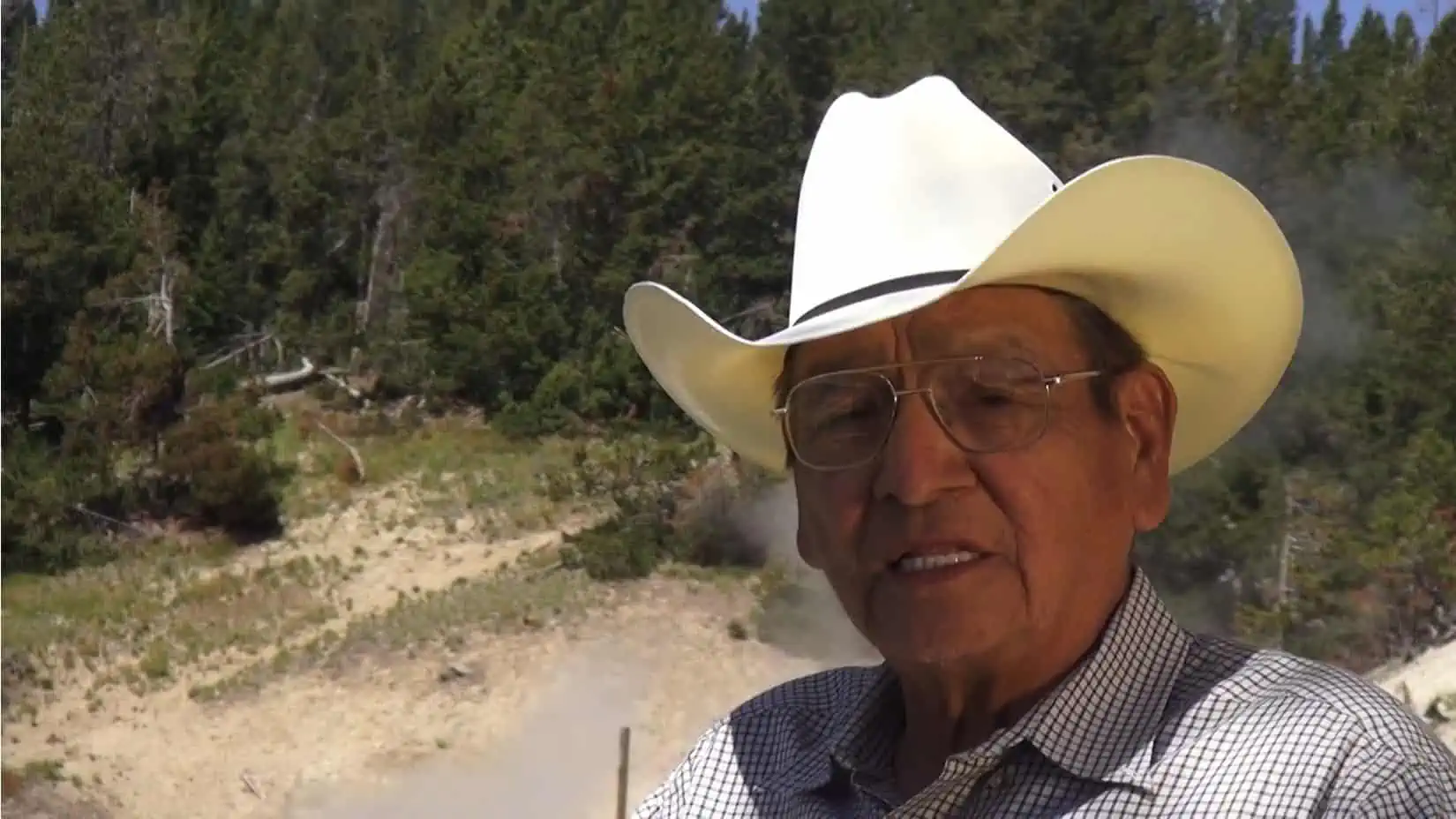

Grand Canyon Speaks Podcast Features Native American Voices

Grand Canyon NP kicks off Native American Heritage Month with the release of season two of Grand Canyon Speaks, a podcast that features Native American voices to explore the history, culture, and stories that are intrinsically linked to the Grand Canyon’s landscape.

The Grand Canyon Speaks podcast, a production supported by the National Park Service, invites listeners to explore the rich tapestry of Indigenous artistry, storytelling, and tradition surrounding the Grand Canyon. Through conversations with artists, community leaders, and cultural advocates, the podcast reveals the powerful bond between art, community, and the land, showcasing the voices of those who carry forward their traditions and inspire others to do the same. Each episode, recorded live before a visitor audience, features a member from one of the 11 associated tribes.

Gerald Dewavendewa

Hopi painter Gerald Dewavendewa shares how his childhood in a Hopi village shaped his view of art. His art celebrates his community, depicting vibrant stories and landscapes that are both personal and communal. He has worked with museums including the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian, and has written and illustrated a children’s book called “The Butterfly Dance.”

Noreen Simplicio

Zuni potter Noreen Simplicio is a dedicated advocate for youth empowerment. She speaks of learning her craft in high school and how she perfected her techniques—both traditional and contemporary. Respect for the landscape is a key part of her work and honoring of her heritage. Her pottery seeks to preserve Zuni culture while adding some of her own contemporary features.

Janet Yazzie

Navajo artist Janet M. Yazzie is renowned for her vibrant contemporary paintings that reflect her deep connection to Navajo traditions and the surrounding landscapes. Drawing inspiration from her roots, Janet’s work captures the beauty of Arizona’s wildlife and night skies with a kaleidoscope of colors. Her work was used for the Grand Canyon Speaks podcast logo.

Zuni Youth Enrichment Project

Lashae Harris, an embroiderer, Chasady Simplicio, a weaver, and Cassandra Tsalate, a potter, are all alumni of the of the Zuni Youth Enrichment Project (ZYEP), a community program designed to connect Zuni youth with their cultural roots. The artists credit ZYEP for guiding them to a craft that allows them to honor their heritage in a personal, creative way. They discuss how traditional art helps them feel empowered and connects them to their community.

Aaron White

Aaron White (Northern Ute/Diné) is a Grammy-nominated guitarist, singer/songwriter, Native American flutist, and flute maker. He co-founded the groundbreaking group Burning Sky, earning a Grammy nomination and Native American Music Award. Known for blending Native American flute with acoustic guitar and drums, his work has been featured in award-winning films. As an accomplished flute maker, his creations are showcased at the Musical Instrument Museum in Phoenix, AZ.

Gregory Hill

Hopi carver and toymaker Gregory Hill offers a different perspective on art as he discusses his work reviving the Patukya, a traditional spinning top. Gregory’s creations inspire childlike wonder in adults, reconnecting them to a sense of joy and simplicity. His efforts have sparked a resurgence in traditional Hopi toys, encouraging other artists to join in preserving this unique form of art.

Zane Jacobs

Zane Jacobs, who is Diné, is the first traditional, local president of Flagstaff Pride. Zane reflects on his experiences growing up near the Grand Canyon and his journey from volunteer to president. His leadership focuses on promoting acceptance, inclusivity, and strengthening Flagstaff’s LGBTQIA2S+ community.

Ciara Minjarez and Shalitha Peaches

Ciara Minjarez and Shalitha Peaches, both members of the White Mountain Apache tribe, discuss food sovereignty. Their work emphasizes the importance of connecting Indigenous communities with traditional food sources, a journey they see as “elders in training,” readying themselves to pass on vital knowledge. Ciara Minjarez is Indigenous Foodways Program Manager at Local First Arizona. Shalitha Peaches is Distribution Manager at Ndee Bikiyaa, The People’s Farm.

Keia Gasper and Jaynie Lalio

Keia Gasper and Jaynie Lalio, 2023-2024 Zuni Royalty, talk about their roles as representatives of the Zuni community. The Zuni Royalty Organization (formerly the Miss Zuni Organization) is dedicated to promoting Zuni culture and traditions among the youth. These titles provide a platform for young Zuni individuals to showcase their talents, promote health, education, and community engagement, and serve as cultural ambassadors for the Zuni people. Keia and Jaynie share how their duties have shaped their character and strengthened their connection to Zuni culture and the Grand Canyon’s sacred landscape.

Top photo by National Park Service

Giants Rising Showcases Redwood Majesty

In Giants Rising, filmmaker Lisa Landers takes us on a journey into the heart of ancient redwood forests. Through stunning visuals and powerful storytelling, Landers sheds light on the urgent need to protect these towering giants, reminding us of their ecological significance, their impact on us as humans, and the role they play in our planet’s future. We spoke to her about the film and her journey in making it.

Lisa, you made a movie about trees! What inspired that and why redwoods in particular?

I think the idea for this film actually first started brewing in my head when I was a 12-year-old kid. I’m from New York and I was on a trip to Northern California and I went to Muir Woods, and it was like game over. I was so smitten, and I was so lit up. I mean, I was a kid who was into fantasy and sci-fi, and I was like, “Oh, oh, this is Middle Earth, I have just landed in Lord of the Rings Land.” I think it just piqued my curiosity so deeply, and my sense of connection with nature. I think in a lot of ways, it is what led me to make a career out of exploring and telling stories about the natural world. The redwoods specifically are what led me to leave my native New York and make my life here in a small redwood grove in Northern California for like 15 years now.

But the film idea—beyond my being 12 years old and just being curious—really started to take root, pun intended, when I started doing short films about redwoods for my work. In the late ’90s, I was sent on an assignment to do a news segment about the woman, activist Julia Butterfly Hill, who was sitting at the top of a redwood tree for two years, in an attempt to protect this beautiful ancient redwood from being logged. And I went there, and I climbed up her tree, and I sat up there with her.

I was so curious about the redwoods and how they do all of the amazing things they do—grow so tall, live so long. But then I was like, wow! How the heck do these trees work their magic on us? I knew that they moved me, but they moved this woman to risk all, to sacrifice so much. At that moment I thought, oh well, gosh! I’m so interested in all the science stuff, but I’m also really interested in this.

I continued making short pieces about different aspects of redwoods, then I had a break in my projects around 2018. I really wanted to tell the kind of epic tale of the redwoods through all these different lenses, not just about the activism to protect them or the impacts of climate change. I wanted to pull it all together, and I went for it.

You mentioned that as a young woman you had an emotional response just to being around the trees, but as we learn more about the science, there’s more to that. Can you speak to that? What are we starting to learn and why is it so beneficial for people to get outdoors? Also, what does that experience do to us?

I went deep into these questions talking to a social psychologist from UC Irvine, who is in the film, to really start to understand what is happening to us physiologically when we are in forests—and specifically among big trees—that really evoke intense feelings of awe. This is someone who has studied that quite a bit. There’s a lot they don’t know, but what they do know is that people all report feeling less stressed, more content, more relaxed.

The brain kind of shifts from being focused on yourself to the outside world, and it creates almost a euphoria. It creates this feeling. What’s so cool is that a social psychologist is asking questions like, why did we evolve to feel that way? Is there something about feeling connected to the natural world that is beneficial to our survival as a species? There’s no answer to that, but it makes you think.

The other thing I did is to really study how the actual physical trees rain down their organic compounds on people when we spend time in the forest. There are all these studies where they put monitors on people and show that your blood pressure goes down, your cortisol goes down and your immunity gets boosted. They can see there are certain white blood cells that target cancer that get a boost. All of these interesting and wonderful things happen, with no side effects.

The third thing I would say is that—and this is something the social psychologist pointed out, based on studies they did with giant sequoias, the cousins of the coast redwoods—they found that people are more compassionate, more cooperative and feel more connected to other people after or during the time they’re spending among trees. They conducted all these tests, and it was like, wow, it just makes us nicer humans to hang out under trees. You could be in any forest, but when you’re in the redwoods, you also get all that awe on top of it because of their verticality, because of their size, and because you know how old they are.

One of the things you discover in the course of the film is that there are linchpins in a much deeper ecosystem. The tree does not live by itself. Can you tell us what you learned about that as you made the film?

That was one of the things that continues to blow my mind. The idea of an ecosystem, that there are all of these interconnections that support everything that lives in this certain area, and the redwoods are no different. But what I didn’t know is how redwoods are very specifically tied to the health of the salmon. There are salmon runs all throughout the redwood ecosystem, and those salmon are totally dependent on the redwoods for shade because they keep the streams cool. They provide little pools when trees fall so there are safe nurseries for the young salmon. And then when the fish dies, all of the nutrients in that fish go into the water and are taken up by the redwood roots and it sustains them. It’s sending all of these nutrients into the trees. There are all these cool connections like that.

If you’ve visited Redwoods you’ve probably noticed they form rings—some people call them fairy rings. Basically, redwoods reproduce by shooting up clones which form a circle around the trunk. It’s not the only way they reproduce, but it’s the main one. Over generations, all of these trees keep shooting up, but they’re really all interconnected underneath. It’s all one organism, sharing resources and communicating. You can be standing in a redwood grove and the entire thing could all actually be one organism.

The largest clone ever discovered to date is 280 trunks, covering an acre and a half. The scientist who’s featured in our film because he focuses on redwood genetics, he was able to look back and figure out when the first seed germinated 30,000 years ago that created these generations upon generations, this family of trees. I could go on and on. But the connectivity is something that is so layered, and I think holds so many lessons for us about survival and resilience.

One of the weirdest stories you tell was this phenomenon of albino redwoods, which I thought was fascinating because these things are like zombies. They shouldn’t be alive but they are, right? Can you explain what that is?

That was the story that first led me to this scientist. I read it, and I was like, what? Because I had seen them. There are these redwood trees, they tend to be smaller than the usual trees, but the leaves, those needles are white, pure white. They have no chlorophyll, and without chlorophyll—which is the thing that plants need to get sunlight and survive—they should be dead.

This scientist has been obsessed with them for a long time and wanted to understand, why is this happening? One of the things he noticed is that these white redwoods appeared in places where there seemed to be a lot of human development, near places where there are railroad tracks or highways or other things.

He took it into the lab and measured it. And what he found was that these white redwoods actually have really high levels of toxins—really high levels to the point where, if it was a green plant, it would die. It’s something that he’s still researching, because again, all the trunks are actually interconnected. So this is like an arm, right? This particular white redwood. And it’s siphoning off all of the things it needs to survive from the green tree. But what if that was an adaptation used to enable the green parts of the tree to flourish? Like taking a hit for the team. Acting as some kind of filtration system. So that’s what he’s studying. And I hope he gets to continue the study because it’s pretty cool.

It’s a fascinating theory, and I hope he proves it because it seems like the sort of thing that would win a science award. You mentioned the threats of human toxins in the soil, but you also documented other threats to redwoods. Can you speak to that?

There were 2 million acres of redwoods when the Europeans started flooding in for the Gold Rush in the 1850s. Beyond gold, they found this remarkable wood, these redwoods. The wood is incredible. It’s rot-resistant. It’s pest-resistant. And it’s a great building material. That itself was pure gold.

Over the course of that time and the following years they logged 95% of that original primeval, never-before-cut forest. What we are left with today are these fragments of old-growth forest. They’re sort of islands and they’re super resilient. Like we were talking about before, these connections in that ecosystem—that’s where they get their resilience from. When you chop them down and you start harvesting them, you don’t have all of that complexity of an ecosystem. They don’t have their resilience.

Ever since the logging of redwoods began there have been calls to protect them because people realize this is not a replenishable resource in our timescale, and they’re so magnificent. And everybody, whether they had quantified the scientific results or not, they felt it.

Starting in the 1800s, people were protesting and trying to save them. This movement to save the redwoods is what launched the movement to create California’s State Park system. There are a few hundred state parks—250 or so—but almost 50 of those actually have redwoods. The oldest California State Park is Big Basin, where some of the oldest, largest primeval redwoods still exist.

There are a lot of conservation organizations trying to buy what’s left of the primeval redwoods. They are also trying to purchase some of the redwood lands that have been turned into timber farms, to be able to restore them, to figure out how we can grow back that old grove forest that once stood there and connect these fragments so that these trees have a greater shot of surviving all of the changes that are coming to our planet.

You documented how redwoods have evolved a pretty amazing resistance to fire, but as fires get hotter and hotter there are situations like the devastating fire in Big Basin. You followed a ranger who spent a lot of time loving that forest and then encountered the worst that can happen.

The fire at Big Basin was devastating, as are all of these other fires that are happening. These fires are sweeping through natural areas, beloved parks, and right through the communities that are adjacent to them. We are all connected in what’s happening now with these fires.

One of the reasons the fires are so intense right now is that there was a policy of not burning anything in parks for a really long time. There were campaigns started 100 years ago, if you see a fire, put it out, not understanding that fire is actually part of the natural cycle of things. The burning actually does all of this good stuff to the soil, and it gets rid of all the stuff that falls on the ground. In a place like Big Basin, they hadn’t really done that for a long, long time, so the whole place was filled with tinder. Lightning strikes and boom! It goes up.

But what’s happening right now, which is pretty exciting, is that there’s a recognition of how important fire is as a tool for keeping forests healthy—something that native tribes in California have always known, but they were forbidden from doing. And so now there is this understanding that what they were doing was really beneficial, and more and more parks and other areas are doing controlled burns. Often now they are working with indigenous partners to do it right. People who have that insight and the knowledge about how to do it.

But it’s still a scary thing. Even setting a controlled fire can be scary for people. So it’s a process for the parks to really talk to people in local communities about what they’re doing, and understand how it may be a little scary, but it is controlled. At the end of the day this is better than waiting for it to happen naturally, because it will and it won’t be pretty.

You followed some amazing characters in the film, including a Native American woman who spoke eloquently about how they were connected to the redwoods. What were some of your favorite characters in the film?

Oh, yeah, I love them all. Of course, there were several who fell on the cutting room floor, and I thought their perspective was so interesting, too. But there was one person in particular who was really neat to be able to spend some time with, and that is Dave Severns who is the Yurok canoe carver. He’s not the main character in the film, but he brings us into the Yurok culture and the Yurok connection to the redwoods.

They carve these beautiful ceremonial canoes out of the redwood fallen trees. They haven’t been able to do it for a long time, because there was a policy that said you can’t take fallen old growth out of the forest, but they were only asking for one a year, and it’s so tied to their honoring of the redwoods. Finally, parks and other places have come around. They need to thin some forests, so things are happening and they’re getting that wood to be able to do it.

The canoe carver brought us into how the honoring of the redwoods and the carving of the canoes is a way they build community. It’s the way they make the younger generations and the tribe feel more connected to each other and to the trees. And he’s a total hoot. I mean, he said, some really really funny things, some things I opted not to keep in the film. But he talked about how special these redwood canoes are to families who make them and have them, and he mentions at one point how they’re so respected that they’re even treated better than some family members. I just thought that was great.

What were the biggest challenges in making this film?

Oh, gosh! So many. Filming in the redwoods is cold and dark a lot of the time, which is hard. Not always the most pleasant to be hanging out for hours and hours at a time. There’s also the fact that the primeval forests were all in parks. So I had to get lots and lots of permissions, and just be really mindful of what I was doing, how I was disturbing the forest—which is a great thing, but it took a lot of extra work. And I had to really convince people that what I was doing was for the benefit of the trees. There are people who go up and they just want to climb to the top of a redwood tree and do all these things. I did have to build relationships and do some convincing.

The other really hard part was that in the middle of making this film, I was diagnosed with breast cancer and everything kind of came to a screeching halt. The only thing I could do to help myself navigate through that period was go out into this redwood grove behind my home and office, and just sit there every day. It was the only place I found where I could really breathe. That sense of perspective these trees gave me is what allowed me to see past all of the anxiety of that moment. And it was real. I mean it really impacted my emotional and mental well-being and helped carry me through that. It also reinforced my dedication to finish the film, which I did, a couple of years later.

On a practical note for those who love your film, what advice do you give to people who want to go out and experience them in person? Many people will know Redwood National Park, because that’s probably the best known. But there are a lot of state parks in California, too.

People know Redwood National Park, it’s true, but that is just one park, and there are so many with redwoods that are just as spectacular. Actually, Redwood National Park is now partnered with three other state parks, Prairie Creek Redwoods, Jedediah Smith Redwoods and Del Norte Coast Redwoods, and they are all spectacular, like primeval, just wondrous.

Everywhere, from Big Sur up and over the Oregon border there are wonderful parks anyone can access. The first park I ever went to, Muir Woods National Monument, is another favorite. What’s so wonderful about Muir Woods is how accessible it is, because getting to these forests you sometimes have to hike in, and they’re not paved. It’s hard to get to. But Muir Woods has this wonderful loop a walkway that is wheelchair accessible. You can be of any age, any ability, and you can go and be in the heart of this primeval redwood forest.

There’s a Redwood Park for everyone, and again, don’t limit it to the national parks or national monuments. I live in a redwood “open space reserve,” and it’s also spectacular. So when those parks get crowded, like Redwood National, you can find a quieter way in, and you can find great resources at places like Save the Redwoods League. They have an interactive map which we also have on our site so you can chart your redwood adventure.

You should start at giantsrising.com, right? Is that the first place to go?

Giantsrising.com. We have a whole section about experiences, which is not just visiting the parks, but things that you can do in the parks. You can do a Yurok canoe tour on the Klamath River through the redwood forest. You can do forest immersions and forest bathing where you go out with a guide. I am now a certified guide. We take people out in parks and other places to just give you permission to play, and really, through your senses, get in touch with your inner child and be with the redwoods. There’s all sorts of things, and we’ll keep posting them as more opportunities and different ways to explore redwoods become available.

What happens next with the film? It’s on the festival circuit. It’s been very well received.

We are still touring, which is great. We’re also starting to do a lot of community screenings. For example, there are communities in and around some of these parks like Big Basin, who have reached out and said, “Hey, we want to show this film in our community center. And we want to talk about fire. We want to talk about how important it is.” So the cool thing is that the film is going to be used by communities in different ways. We’re trying to provide them the tools they need to have these ongoing conversations.

The film is going to be distributed internationally soon. It is starting to screen internationally, which is pretty cool. Who knew that redwoods were going to be of interest? But you know, I think the redwoods are this portal to feeling connected to nature, or to the woods that are in your backyard. I think that resonates with a lot of people. And they’re so iconic. We are working on finding a North American distribution partner so that people will be able to watch this in the comfort of their own homes. Hopefully that’ll be there soon. We’ll put updates on the website. And if people sign up for our newsletters, they can find out more about that, too.

What key takeaways would you hope people leave the film with?

Three things. The first is that there are a lot of organizations and parks doing really important work to ensure the redwood forests can thrive for many years to come. But they need our support, whether it’s your time volunteering, or financial support. I hope people walk away with that—or just by voting for more protection for forests, or things like that.

Number two, there are more people and organizations starting to embrace the value of indigenous insights and knowledge when it comes to managing our forests and other natural landscapes. It’s gone on for too long that many of these tribes have not been at the table, and I think our natural landscapes have suffered because of that. So I hope there are changes in the air for this.

And then, thirdly, I just hope people get out into the woods wherever they are and just soak it up. Soak up all of those organic compounds, the awe, the wonder, the everything. It’s a gift, and it doesn’t have to be redwoods. I hope that people, after watching the film, go out and remember what it was like when they connected with that tree they used to climb as a kid, or a forest that’s had some significance to them, and just make more of those connections. Because if you don’t feel that connection, it’s a loss for you. But also that connection is probably what’s going to get you to be a little bit more engaged and involved in making sure we steward these forests, and these natural places, as they need to be.

5. Del Norte Coast Redwoods State Park

Just south of Crescent City, Del Norte Coast Redwoods State Park encompasses a variety of ecosystems, including old-growth forests, coastal habitats, and riverine environments, supporting diverse wildlife such as elk, black bears, and numerous bird species. In addition to coast redwoods reaching heights of over 350 feet, there are several trails for hiking, including the popular Stout Grove, which offers views of ancient redwoods. The park’s coastal location provides views of the Pacific Ocean along with opportunities for beachcombing and tidepooling.

4. Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park

Located in Humboldt County, California, this park is part of the Redwood National and State Parks. The views of the redwood trees are just a short walk from the visitor’s center. There are 75 miles of hiking trails, bike trails, scenic drives, campgrounds, and picnic areas. Although the park is known to have some of the best views of the oldest redwoods, it is also known for Gold Bluffs Beach and Fern Canyon, a tranquil creek surrounded by walls of ferns.

3. Big Basin Redwoods State Park

Big Basin is located in the heart of the Santa Cruz Mountains, just 9 miles away from the picturesque town of Boulder Creek, CA, and 35 miles away from San Jose, CA. Big Basin is California’s oldest state park and is home to the largest continuous stand of ancient coast redwoods south of San Francisco. Some trees at Big Basin are over 2,000 years old. Big Basin is also home to a variety of other wildlife, including banana slugs, deer, frogs, raccoons, and coyotes.

2. Jedediah Smith State Park

Jedediah Smith State Park joined Redwoods National Forest in 1994 and has become a popular site to see the Redwood Trees. The Park is located in Crescent City, and contains 7% of the world’s remaining old-growth redwoods, including some of the world’s largest specimens. Visitors can hike through a rainforest, fish, snorkel, or kayak in the Smith River, drive on Howland Hill Road, or enjoy a campfire.

1. Muir Woods National Monument

Muir Woods National Monument is in Marin County, just a few miles north of San Francisco. The Redwoods trees found in the park and along the coast of California are the tallest living on Earth and the last remaining ancient redwood trees in the Bay Area. Muir Woods is also home to the Northern Spotted Owl and Northwestern pond turtles, one of two remaining native freshwater turtles in California.

In top photo, photographer Sarah Bird walks among the redwoods of California

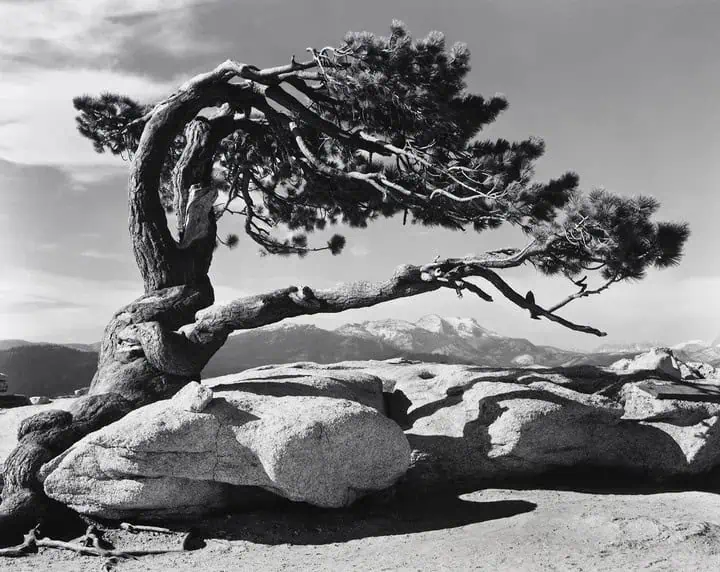

Capturing Yosemite: Ansel Adams’ Vision

One of the best-known photographers of the 20th century, Ansel Adams’ iconic photos of Yosemite National Park and the American West helped advocate for the preservation of the natural environment. His photos of Yosemite, a place that profoundly influenced his life and career, are among his most celebrated works.

Early Encounters

Adams first visited Yosemite National Park in 1916 at the age of 14. Armed with a Kodak Brownie camera, he was immediately captivated by the park’s majestic landscapes. This initial visit sparked a lifelong passion for photography and the natural world. The beauty of Yosemite’s granite cliffs, towering sequoias, and cascading waterfalls provided endless inspiration for Adams, who returned to the park year after year.

In 1919, Adams joined the Sierra Club, an environmental organization dedicated to preserving the wilderness. He spent several summers working as the caretaker of the Sierra Club’s LeConte Memorial Lodge in Yosemite Valley, where he honed his photographic skills and developed a profound appreciation for the park’s natural beauty.

Adams’ early works in Yosemite were characterized by their sharp focus and high contrast, capturing the park’s dramatic landscapes in stunning detail. He often sought out scenes that highlighted the interplay of light and shadow, capturing the essence of the natural world in its most pristine form. One of his most famous early photographs, “Monolith, the Face of Half Dome,” taken in 1927, exemplifies his ability to convey the grandeur and majesty of Yosemite’s iconic landmarks.

Technical Mastery and Artistic Vision

Adams was not only a master of composition but also a technical innovator. He developed the Zone System, a photographic technique that allowed him to control the exposure and development of his images with precision. This system enabled Adams to achieve a remarkable range of tones in his black-and-white photographs, from the deepest blacks to the brightest whites.

His meticulous approach to photography was matched by his artistic vision. Adams saw beyond the physical features of Yosemite, capturing the essence of the park’s wildness and beauty. His images evoke a sense of awe and reverence, inviting viewers to appreciate the natural world in all its splendor.

Conservation Efforts

Adams’ work in Yosemite was not just about creating beautiful images; it was also about advocating for the preservation of the natural environment. His photographs played a crucial role in the American conservation movement, raising awareness about the importance of protecting national parks and wilderness areas.

In the 1930s, Adams’ photographs were used to promote Yosemite and other national parks, helping to secure their protection and funding. His images were featured in publications, exhibitions, and books, reaching a wide audience and inspiring a greater appreciation for the natural world.

Legacy and Impact

Adams’ legacy in Yosemite is enduring. His photographs continue to be celebrated for their technical excellence and artistic beauty. They serve as a powerful reminder of the importance of preserving our natural heritage for future generations.

The Ansel Adams Gallery, located in Yosemite Valley, stands as a testament to his enduring influence. The gallery showcases Adams’ work and promotes the appreciation of photography and the natural world. It is a place where visitors can connect with Adams’ vision and gain a deeper understanding of the park that inspired him.

Top photo of Ansel Adams in Yosemite National Park c. 1942 (Photo courtesy the Cedric Wright Family)

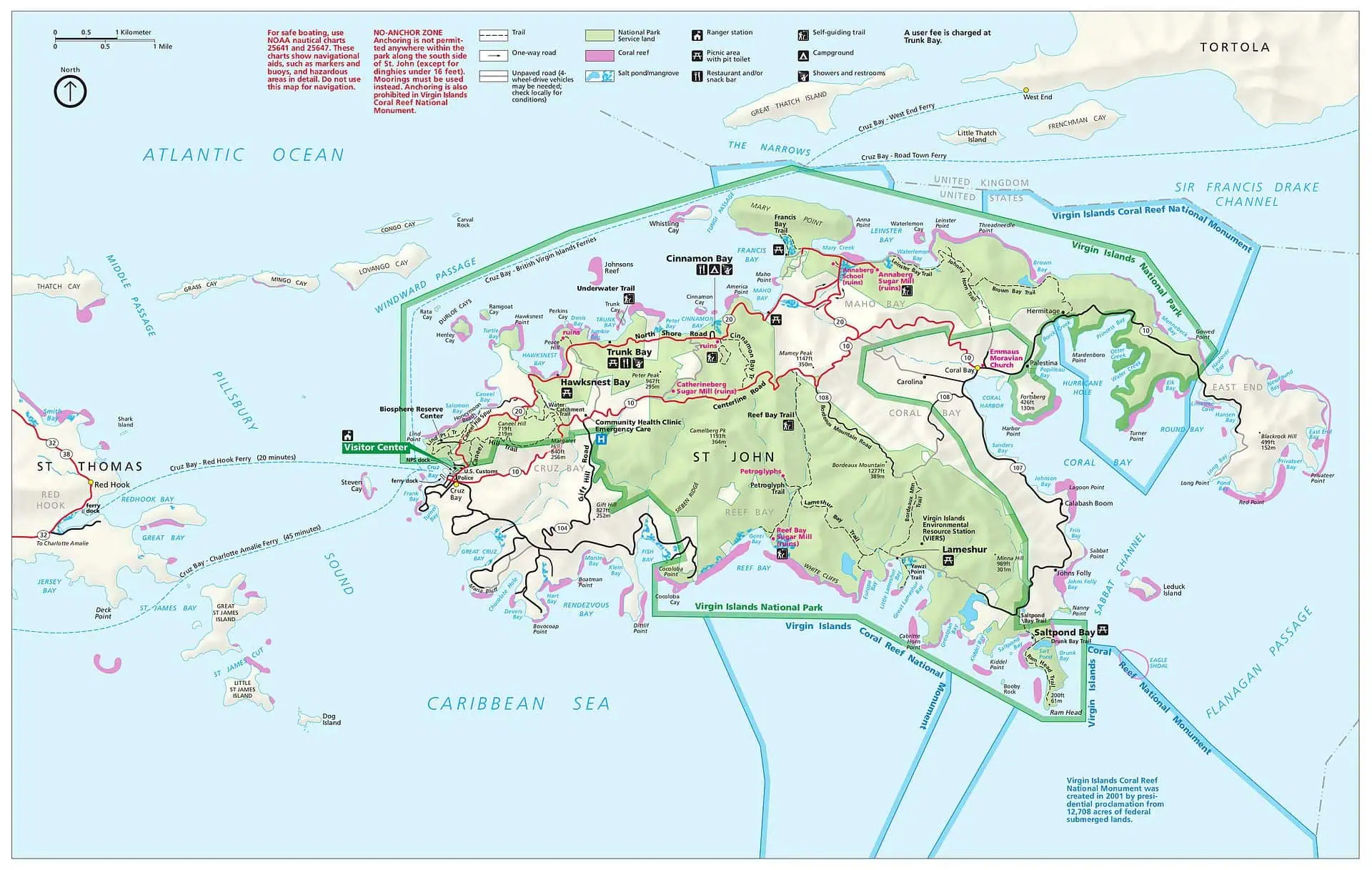

Trivia Contest: Virgin Islands National Park

Nestled in the heart of the Caribbean, Virgin Islands National Park is a treasure trove of natural beauty, rich history, and vibrant marine life. How much do you know about it? Read on, then try your hand at our Virgin Islands Trivia Contest.

How Virgin Islands National Park Was Born

The journey toward creating Virgin Islands National Park began in the mid-20th century when environmental conservation was gaining momentum in the United States. Laurance Rockefeller, a prominent businessman, conservationist, and philanthropist—and grandson of oil baron John D. Rockefeller—played a pivotal role in the establishment of Virgin Islands National Park.

Captivated by the island’s natural beauty during a visit in the 1950s, Rockefeller recognized the need to preserve the island’s unique environment for future generations to enjoy. At the time, St. John was a largely undeveloped and sparsely populated island, making it an ideal candidate for conservation.

Rockefeller’s commitment to conservation led him to purchase large tracts of land on St. John Island. His goal was to protect the island’s natural resources and prevent unchecked development. In 1956, Rockefeller donated approximately 5,000 acres of this land to the National Park Service, laying the foundation for what would become Virgin Islands National Park.

Rockefeller’s generous donation, combined with additional land acquisitions by the government, led President Dwight D. Eisenhower to sign the legislation establishing Virgin Islands National Park on August 2, 1956. This marked a significant milestone in the history of American conservation, as it was one of the first national parks to be created outside of the continental United States.

The establishment of the park came with its challenges. The local community had mixed reactions, with some residents concerned about the impact on their livelihoods and traditional ways of life. However, over time, many came to see the value of preserving the island’s natural resources and the potential benefits of tourism.

Today, Virgin Islands National Park is a beacon of conservation success. It protects diverse habitats, from lush tropical forests and white sandy beaches to vibrant coral reefs teeming with marine life. The park also safeguards important cultural sites, including ancient petroglyphs left by the Taino people and historic plantations that tell the story of the island’s colonial past.

Underwater Treasures

Many visitors to Virgin Islands National Park might not realize that some of the park’s most captivating treasures lie beneath the turquoise waves. Approximately 60% of Virgin Islands National Park is underwater, offering an aquatic paradise filled with vibrant marine life, stunning coral reefs, and hidden wonders waiting to be discovered.

The park’s diverse marine environment comprises habitats ranging from seagrass beds and mangrove forests to intricate coral reef systems. These underwater ecosystems are home to a variety of marine species, making the park a haven for snorkelers, divers, and marine enthusiasts. Among the park’s underwater residents are colorful tropical fish, graceful sea turtles, playful dolphins, and even the occasional nurse shark, all coexisting in a delicate balance.

Visitors can engage with the park’s marine world through a variety of activities, from guided snorkeling and diving tours to kayaking and paddleboarding. These experiences offer visitors a closer look at the park’s coral reefs, which include elkhorn, staghorn, and brain coral formations, which are vital to the health of the marine ecosystem. They provide shelter and food for countless marine species, support commercial and recreational fisheries, and protect the shoreline from erosion by buffering the impact of waves.

Virgin Islands National Park is dedicated to marine conservation efforts, working tirelessly to preserve these precious underwater environments. Initiatives include coral restoration projects, marine habitat protection, and public education programs aimed at promoting sustainable tourism and environmental stewardship. By raising awareness about the importance of marine conservation, the park ensures that its underwater wonders can be enjoyed by future generations.

The Taino People

Long before the arrival of European explorers, the picturesque island of St. John was inhabited by the Taíno people. These indigenous inhabitants left a permanent mark on the land, with their culture, art, and way of life continuing to inspire and educate us today.

The Taíno were a branch of the Arawak people who originally migrated from the Orinoco Basin in South America. By the time of European contact in the late 15th century, the Taíno had established thriving communities across the Greater Antilles and the northern Lesser Antilles, including the Virgin Islands.

The Taíno society was structured and well-organized, with communities led by a cacique (chief). They lived in bohíos (circular houses) made of wood and thatch, and their villages were often strategically located near fertile land and water sources. The Taíno practiced agriculture, cultivating crops such as cassava, maize, sweet potatoes, and tobacco. They were also skilled fishermen and navigators, crafting canoes from tree trunks to travel between islands.

The arrival of Christopher Columbus in 1493 marked the beginning of significant changes for the Taíno people. The Europeans’ colonization efforts led to the decline of the Taíno population due to disease, enslavement, and violent conflict. Despite these hardships, the Taíno legacy endured through cultural exchange and the blending of traditions, which influenced the Caribbean’s cultural mosaic.

Today, Virgin Islands National Park serves as a custodian of Taíno heritage. The park’s archaeological sites and petroglyphs stand as a testament to the Taíno’s presence and resilience. Visitors to the park can explore these historical landmarks and gain a deeper understanding of the Taíno’s way of life and their connection to the land.

Trunk Bay Underwater Snorkel Trail

Imagine swimming through crystal-clear waters, surrounded by vibrant coral reefs and schools of tropical fish, with the sun casting shimmering patterns on the seabed below. This heavenly scene is a reality at Trunk Bay, one of the most picturesque spots in Virgin Islands National Park. Famous for its pristine beach and stunning underwater scenery, Trunk Bay is home to the unique and captivating Underwater Snorkel Trail—a must-visit destination for snorkelers and nature enthusiasts.

The Trunk Bay Underwater Snorkel Trail is a 225-yard-long underwater path marked by interpretive plaques that guide snorkelers through the coral reefs. These plaques provide interesting facts about the various coral formations and marine species that inhabit the area.

As you snorkel along the trail, you’ll encounter an array of coral types, including elkhorn, staghorn, and brain coral, each hosting a diverse community of marine life. Parrotfish, angelfish, sergeant majors, and other colorful fish dart among the coral, while sea fans sway gently with the currents. The trail’s clear, shallow waters make it accessible for snorkelers of all levels, from beginners to seasoned enthusiasts.

Trunk Bay Underwater Snorkel Trail provides an unforgettable journey through some of the Caribbean’s most stunning underwater landscapes. As you swim among the coral reefs and colorful fish, you’ll gain a deeper appreciation for the beauty and fragility of the ocean’s ecosystems.

Annaberg Sugar Plantation

Located within the lush landscapes of Virgin Islands National Park, the Annaberg Sugar Plantation stands as a poignant reminder of the island’s colonial past. Once a thriving center of sugar production, this historic site now offers visitors a glimpse into the complex history of the Caribbean.

The Annaberg Sugar Plantation was established in the late 18th century, during a time when the Caribbean was a major hub for sugar production. Sugar, often referred to as “white gold,” was a highly lucrative commodity, driving economic growth and development in the region. The plantation relied heavily on the labor of enslaved Africans who worked under harsh conditions to cultivate sugarcane and produce sugar, molasses, and rum.

The site features several well-preserved structures that provide insight into the daily workings of the plantation, including the sugar mill, boiling house, slave quarters, and the overseer’s house. The plantation is more than just a historical site; it is a symbol of the cultural and social dynamics of its time. The plantation system was a significant part of the Caribbean’s colonial economy, but it also played a crucial role in shaping the cultural landscape of the region. The blending of African, European, and indigenous influences gave rise to a unique Caribbean culture that is still evident today.

Today, the Annaberg Sugar Plantation is managed by the National Park Service and is open to the public. Visitors can take guided tours that provide detailed historical context and personal stories of the people who lived and worked on the plantation. The site also features interpretive signs that offer insights into the various processes and structures found on the plantation.

Top photo of Honeymoon Beach and Salomon Bay on St John, Virgin Islands, by Bradley Furlow

Yosemite: Beyond the Valley

Yosemite Valley provides exciting adventures for hikers, but peak season crowds can diminish the experience. Thankfully, many hidden gems lie beyond the valley, ready to be discovered.

Situated in California’s famed Sierra Nevada Mountains, the stunning waterfalls and high-elevation views of Yosemite National Park are a hiker’s dream.

Carved by ancient glaciers, its iconic U-shaped valley features unique topography, including glacial megablocks, waterfalls, and domes. The park is among the top 10 most visited national parks in the United States, boasting millions of visitors every year.

If you’re planning a trip to Yosemite, you’re probably thinking about doing the popular Yosemite Falls Trail with its breathtaking views of the valley, Half Dome, and Upper Yosemite Fall. Or maybe the Mist Trail is on your itinerary with its intimate view of Vernal Fall, vibrant plant life and dramatic ascent up a giant staircase to the top.

Yosemite Valley offers tons of unique and thrilling experiences. However, the crowds of hikers in popular seasons can detract from your experience. Thankfully, there are dozens of great hikes—and plenty of other adventures—in less-visited areas beyond the valley.

1. Wawona

Wawona is an expansive mid-elevation basin in the southern part of the park. It’s home to giant sequoias and one of the largest mountain meadows in the High Sierra.

The area was originally inhabited by the Ahwahnechee, part of the Southern Sierra Miwok tribe. Many Native American artifacts can still be found, including mortar rocks used to prepare food, as well as arrows and spear tips that serve as reminders of the region’s rich indigenous history. (Remember to always leave artifacts where you find them.)

The town of Wawona is located entirely within Yosemite and precedes the establishment of the park. It serves as a gateway to the southern areas of the park and is known for several historic buildings, including the Wawona Hotel, a classic Victorian resort and National Historic Landmark.

Wawona’s clear rivers are perfect for water activities in the summer. Its abundant wildlife—including rare birds like the Great Gray Owl and aquatic creatures such as Western Pond Turtles—add natural beauty to its streams. For photographers, relaxed vacationers and thrill seekers, this location earns a spot on every visitor’s itinerary.

Popular attractions

Chilnualna Falls: A long and steep hike with a rewarding payoff—a comparatively deserted trail boasting beautiful cascades and three picturesque waterfalls. The popular Mist Trail, on the other hand, has only two waterfalls and swarms of people blocking your view!

Wawona Swimming Hole: During the late spring and summer months, enjoy tubing down rapids or read a book while relaxing in a cold, crystal clear river. There is also a swinging bridge at this location for the daredevils of your group.

Yosemite History Center: Are you looking to complement your hiking trip with an enriching historical experience? See rustic cabins and unique exhibits—such as the long-abandoned Chinese Laundry—and get a fascinating glimpse into the community that flourished during the Gold Rush.

2. Hetch Hetchy Valley

Just over an hour’s drive up to the quiet northwest corner of the park, this area is known for biodiversity and grandeur that rival Yosemite Valley. Hetch Hetchy is perfect for hikers and features impressive waterfalls, sprawling granite cliffs and domes, and abundant wildflowers due to its low elevation.

Like Wawona, this beautiful valley was cherished by indigenous people until a decision was made to flood it to create the reservoir. The Hetch Hetchy Reservoir was formed by the O’Shaughnessy Dam on the Tuolumne River and serves as a water supply for the city of San Francisco and surrounding areas. The valley was historically home to the Miwok and Paiute Native American tribes and had significant cultural and environmental importance to these indigenous communities. The construction of the dam has been a subject of controversy since its inception in the early 20th century.

The name “Hetch Hetchy” translates to “edible grasses,” likely due to its abundance of acorns and edible plants. With one of the longest hiking seasons in the park, Hetch Hetchy offers visitors the flexibility to explore its trails almost year-round, providing hikes of all difficulty levels.

Popular Attractions

Wapama Falls Trail: Hike along the reservoir’s edge on a moderate 5-mile round-trip, with a great view at the base of Wapama Falls. During spring, adventurous hikers can cross the bridges below the falls and experience a refreshing mist from the cascade.

O’Shaughnessy Dam: Though its 1919 construction spurred controversy, this 430-foot dam remains an impressive sight. Hikers can take a short, 2-mile hike up to Lookout Point, offering a sweeping view of the reservoir and its backdrop of glacier-carved granite cliffs. The Wapama Falls trail also takes hikers on a scenic walk across the dam.

Evergreen Lodge: After a long day of hiking and spectacular views, hikers can kick back at a tranquil cabin in the woods, cool off in the pool or hot tub, lay in a hammock, or if they still have energy, enjoy the thrill of Evergreen’s ziplines. Known for its terrific restaurant, Evergreen Lodge is ideal for tired visitors ready to relax.

3. Tuolumne Meadows

Prefer the tranquility of high elevation views? Accessible via Tioga Road, Tuolumne Meadows involves an 8,600-foot ascent to a subalpine meadow. This magnificent area features picturesque lakes, trails up its distinctive domes, and a backdrop of mountain peaks accessible by cross-country skis.

Known for its amazing campsites, gorgeous alpine lakes, and secluded hikes, Tuolumne Meadows appeals to novice hikers and families who want to explore the scenery without much of a challenge.

Fun fact: The water sources at Tuolumne Meadows are so clean they require minimal water treatment. The Tuolumne River originates here, flowing through the meadows and eventually reaching Hetch Hetchy which accounts for the vast majority of drinking water in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Popular Attractions

Pothole Dome: Situated on the western edges of the meadow, a short half-hour hike leads up a smooth, granite dome with panoramic views of Tuolumne Valley, the river, and the surrounding mountains. This spot is rarely crowded, giving hikers a unique opportunity to enjoy Yosemite’s peace and quiet all to themselves.

Cathedral Lakes: For hikers who prefer a longer journey, this 8.2-mile round-trip features the pristine lakes of the High Sierra, reflecting the stunning alpine scenery on the famed John Muir Trail. One of the most popular attractions in Tuolumne Meadows, the subalpine landscape sets the meadows apart from other parts of Yosemite.

Tenaya Lake: Looking for a prime swimming spot without the effort of a long hike? Tenaya Lake—named after Chief Tenaya, of the Yosemite Indians—is 7 miles west of Tuolumne Meadows on Tioga Road. It offers visitors rocky and sandy beaches, as well as canoeing and tubing.

4. Sentinel Dome and Taft Point

This location is often ignored by visitors, partly because of the popularity of neighboring trails, and partly because of its initially unkempt appearance with fallen trees and sparse vegetation.

However, a short and easy-to-moderate hike rewards visitors with arguably the most fantastic view of Yosemite. Located along the road up to Glacier Point, Sentinel Dome offers a 360-degree view of the park including Half Dome, El Capitan, Yosemite and Nevada Falls, and much more.

Watch how NatureBridge connects young people to the wonder and science of Yosemite.

Popular Attractions

Fallen Jeffrey Pine: The fallen Jeffrey Pine on Sentinel Dome is one of Yosemite’s most photographed trees, celebrated for its poetic beauty and twisted, rugged appearance. Perched on the park’s second-highest point, the iconic tree, which died in 2003, was shaped by its harsh, high-altitude environment.

View this post on Instagram

A post shared by Felicia Wong | Family Adventures | Outdoors | Travel (@everydayadventurefam)